‘Only Case’ of CMT2 With Type 4 Symptoms Reported in Man, 63

Patient with CMT2K developed worse lung function, acute voice problems

Written by |

A new report describes the case of a 63-year-old man diagnosed with an atypical, severe form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 (CMT2), with overlapping symptoms of the rarer CMT type 4.

Genetic testing showed the man had the subtype CMT2K, caused by mutations in the GDAP1 gene, but with quickly worsening symptoms.

Such rapidly progressive disease at his age “is a unique presentation of CMT2K,” the scientists wrote, noting the patient developed lung function worsening and voice dysfunction that are common in CMT4A. While CMT2 types usually have a slow progression, CMT4 “exhibits severe disease with an early onset,” the team noted.

“To our knowledge, we present the only documented case of CMT2K with adult-onset rapidly progressive respiratory failure and acute vocal cord dysfunction,” the researchers wrote.

The report, “Autosomal dominant GDAP1 mutation with severe phenotype and respiratory involvement: A case report,” was published in the journal Frontiers in Neurology.

A unique case

CMT is caused by mutations that affect the normal functioning of peripheral nerves, which supply movement and sensation to the arms and legs. The disease can be classified into several types based on factors such as which genes are mutated, the inheritance pattern, and the the speed of nerve conduction.

While people with CMT4 show damage to myelin — the insulating fat-rich layer surrounding nerve fibers — those with CMT2 have mutations that disrupt the structure and function of axons, the long projections of nerve cells that conduct signals to the next nerve cell or muscle cell.

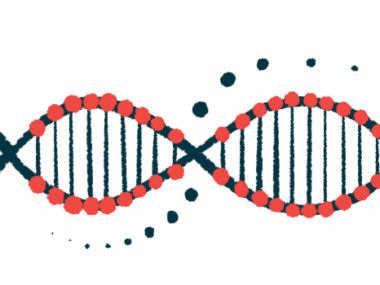

Mutations in the GDAP1 gene — which encodes a protein that contributes to energy production in cells — has been linked to two distinct subtypes, CMT2K and CMT4A.

While CMT2K is caused by dominantly inherited mutations in the GDAP1 gene, in the case of CMT4A, the mutations are recessively inherited. In dominant inheritance, a single copy of the mutated gene is sufficient for the disease to develop, while in recessive inheritance the disease only occurs if a patient has mutations in both gene copies — one from each biological parent.

In CMT4A, symptoms typically start in childhood, and include severe damage to peripheral nerves (neuropathy), often leading to wheelchair dependence by early adulthood. At later stages, patients commonly have vocal cord paresis, or impaired motion of the vocal folds, and weakness of the diaphragm — a muscle located below the lungs and key for breathing.

CMT2K — like all CMT2 types — generally has a milder presentation, characterized by a slow progression, and symptom onset in adulthood. In addition, most CMT2K patients are able to walk throughout their lives.

Now, researchers at Florida Atlantic University described an atypical case of a patient with severe CMT2K with rapidly progressive nerve damage, respiratory failure, and the voice disorder dysphonia.

The man had sought treatment for a heavy chest sensation and dysphonia. He had been diagnosed with CMT one year before and his clinical history included progressive paresthesias, or a burning or prickling sensation, cramps, and weakness in the right leg that spread to the left leg and arms.

The patient had needed a wheelchair most of the time since his CMT diagnosis.

He underwent genetic testing for 81 genes linked with peripheral nerve diseases, which revealed a mutation in one of the copies of the GDAP1 gene. According to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guideline, this mutation was deemed as pathogenic, or causing disease.

His family history included one brother diagnosed with CMT at age 5 and one niece diagnosed at age 4. Yet, in both cases, symptoms were milder and included difficulty walking, arched feet, and leg muscle wasting. His parents had no signs of CMT. This pattern was consistent with dominant inheritance, the investigators noted.

Testing for clues

Neurological tests revealed the man had weakness in his arms, hands and right wrist muscles, with compromised handwriting. His ability to flex his feet was impaired and he presented areflexia, or absence of reflexes, with decreased pinprick, vibration and thermic sensation in his arms and legs up to the knees and wrists. He scored 24 out of 36 in the CMT neuropathy scale, indicative of severe disease.

Chest X-ray and cardiac examination generally did not show abnormalities, although the patient had a mildly rapid breathing rate. Lab tests were unremarkable. MRI scans of the brain and spine, as well as a chest CT scan, also were normal.

Nerve conduction studies revealed evidence of damage to the right median nerve and to the ulnar nerve, which relay information to the forearm and hand. The patient further showed severe, generalized sensory and motor nerve cell damage in the legs.

He was advised to undergo speech therapy due to his reduced speaking ability (phonation) and weak cough. Because no imminent threat to the patient’s life was found, he was discharged.

After having been lost to follow-up, he returned to the hospital three weeks later due to worsening respiratory failure and dysphonia, and received ventilation support for breathing due to low blood oxygen levels. Chest X-rays showed a mild elevation of part of his diaphragm. Further tests excluded autoimmune conditions, substance abuse, infection, lung blood clots, spinal cord injury and brain alterations as causes for the respiratory insufficiency.

Due to hard-to-treat hypercapnia — high carbon dixode levels in the blood — the patient’s mental status aggravated. Intubation was not performed, at his request, and he ultimately was transferred to hospice care, six weeks after his first hospital visit.

Overall, this case suggests that the “presentations of various types of CMT may extend beyond our current genotypic cognizance,” the researchers wrote.

“This case will hopefully serve to motivate further research, disease understanding, and treatment optimization for those diagnosed with Charcot Marie Tooth,” they concluded.