Hearing Difficulties in CMT Linked to Nerve Signaling Problems in Study

Written by |

People with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) may have difficulties in understanding speech, even in the absence of hearing loss, caused by problems with the nerve cells that carry signals from the ears to the brain, a study suggests.

The study, “Psychoacoustics and neurophysiological auditory processing in patients with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease types 1A and 2A,” was published in the European Journal of Neurology.

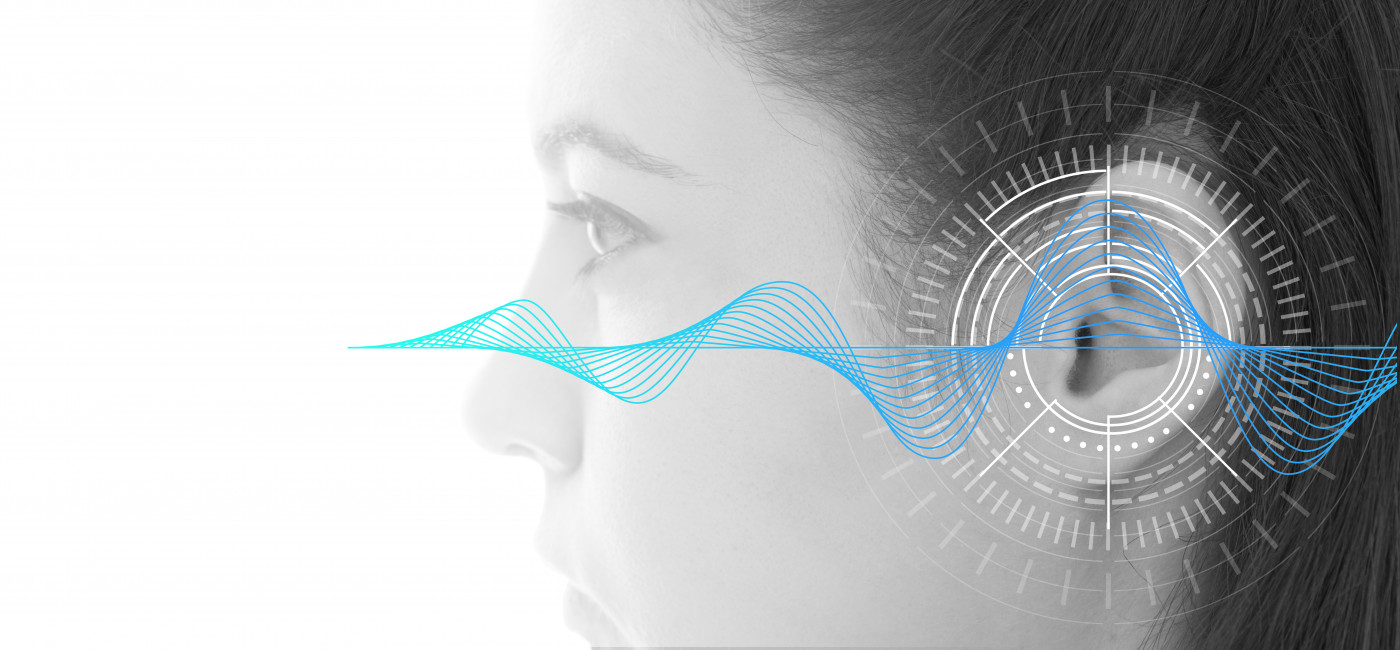

When sound waves reach the ear, they are picked up by specialized cells called hair cells. The vibrations from sound waves trigger chemical changes in these cells, ultimately resulting in neurons sending an electrical signal from the ears to the brain. Collectively, this is the basic process of hearing.

Hearing problems are relatively common among people with CMT. Previous research has suggested that these people are often able to detect simple sounds normally, but can have difficulty making sense of more complex noises — for example, hearing a person talking amid background noise (ambient sounds).

Since CMT is characterized by damage to nerve cells, it is possible that abnormalities in the neurons carrying signals from the ear to the brain account for these hearing problems. However, little research has been done into the neurological changes that accompany hearing problems in CMT.

A battery of hearing tests were given to 58 people with CMT: 43 with CMT type 1A (CMT1A, caused by duplication of the gene PMP22), and 15 with CMT type 2A (CMT2A, caused by mutations in the MFN2 gene). These patients had no apparent hearing loss.

For reference, hearing tests were also administered to 58 people without CMT, serving as controls. Study participants were about 30 years old, on average, and there was a roughly even number of males and females.

Confirming previous work, test results for people with CMT were similar to controls regarding the hearing of single tones or speech in the context of a quiet environment. However, CMT patients did significantly worse on tests of speech heard in a noisy environment, as evidenced by significantly higher speech-to-noise ratios (SNRs). The average SNR was -2.8 decibels for CMT1A, -2.7 decibels for CMT2A, and -3.3 decibels for controls.

“Although all participants had normal audiograms, CMT1A and CMT2A patients had difficulty understanding speech in a noisy background compared to healthy controls,” the researchers wrote.

In addition to determining hearing ability, the researchers measured auditory frequency-following responses (FFRs) in participants. FFRs, taken through electrodes placed on the scalp, are basically a measurement of the electrical signals sent along neurons when hearing takes place.

Results of these measurements indicated that, relative to controls, electrical signals had a lower amplitude in CMT patients, meaning that neurons were firing less strongly in these people, though timing of neuronal firing remained similar to that of controls.

“Our finding provided evidence that the deficit in auditory temporal processing is probably related to a reduction in the firing rate of the averaged nerve response over time,” the researchers wrote.

This difference could be caused by the neurons themselves getting fewer signals, or being unable to “sync up” with one another to send a clear signal to the brain. Notably, there were a few differences in FFRs between CMT1A and CMT2A, likely as a result of differences in the specific type of neuron damage that characterize these types of CMT.

The researchers also created statistical models to see whether hearing abnormalities were more common in more advanced disease. While many hearing features correlated with CMT progression, most of these correlations were not statistically significant after accounting for patients’ age.

The exception was audio temporal resolution — being able to discriminate between different sounds heard close together in time. This significantly correlated among patients with factors like age at onset, disease duration, and poorer motor neuron function.

“In summary, our study found that CMT1A and CMT2A patients with normal audiograms had abnormal auditory processing compared to the healthy controls,” the researchers concluded. “Although there was a somewhat different underlying pathophysiology in the auditory dysfunction between CMT1A and CMT2A patients, both CMT types reduced the firing rate of the averaged nerve response.”

This finding may have implications for the care of people with CMT, the researchers added.

“In the clinical management of CMT patients with hearing complaints, it is important to recognize that even among CMT patients without audiometric evidence of hearing loss, the encoded acoustic signal may lack the fidelity needed for speech perception in a noisy background,” they wrote,