CMT Research Foundation to Develop Precision Medicine Approach for Subtypes

The CMT Research Foundation has launched a new research program that will seek to develop a precision medicine approach to treat people with Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease, the foundation announced in a press release.

The approach focuses on silencing the gene that is causing the disease in each disease subtype, and replacing it with a functional gene. While expected to treat multiple CMT subtypes, researchers will begin by investigating it as a treatment for CMT type 2E, which is caused by mutations in the NEFL gene.

The research will be conducted by Chris Lorson, PhD, and Michael Garcia, PhD, of the University of Missouri, who have complementary expertise in CMT animal models, neurofilament biology, and genetic manipulations.

CMT is a group of inherited conditions that affect the structure and function of the nerves in the peripheral nervous system, which control movement and sensation. There are dozens of CMT subtypes, depending on the specific gene that is mutated.

In some of these subtypes, gene therapy approaches that remove the mutated gene are enough to alleviate disease symptoms. In others, however, the abnormal gene is needed for essential cellular functions, and inserting a functional gene into the patients’ genome also is needed.

This is the case with CMT2E, in which mutations in the NEFL gene result in the production of an abnormal form of the neurofilament light chain (NfL) protein — a subunit of neurofilaments, which are needed for the structural stability and growth of nerve cell fibers, or axons.

This abnormal protein not only is unable to assemble into filaments, it also forms protein clumps that impair other neurofilament subunits from forming these filaments. That is why patients require gene therapy approaches that shut down the abnormal gene — and prevent it from giving harmful instructions to cells — and replace it with a functional one.

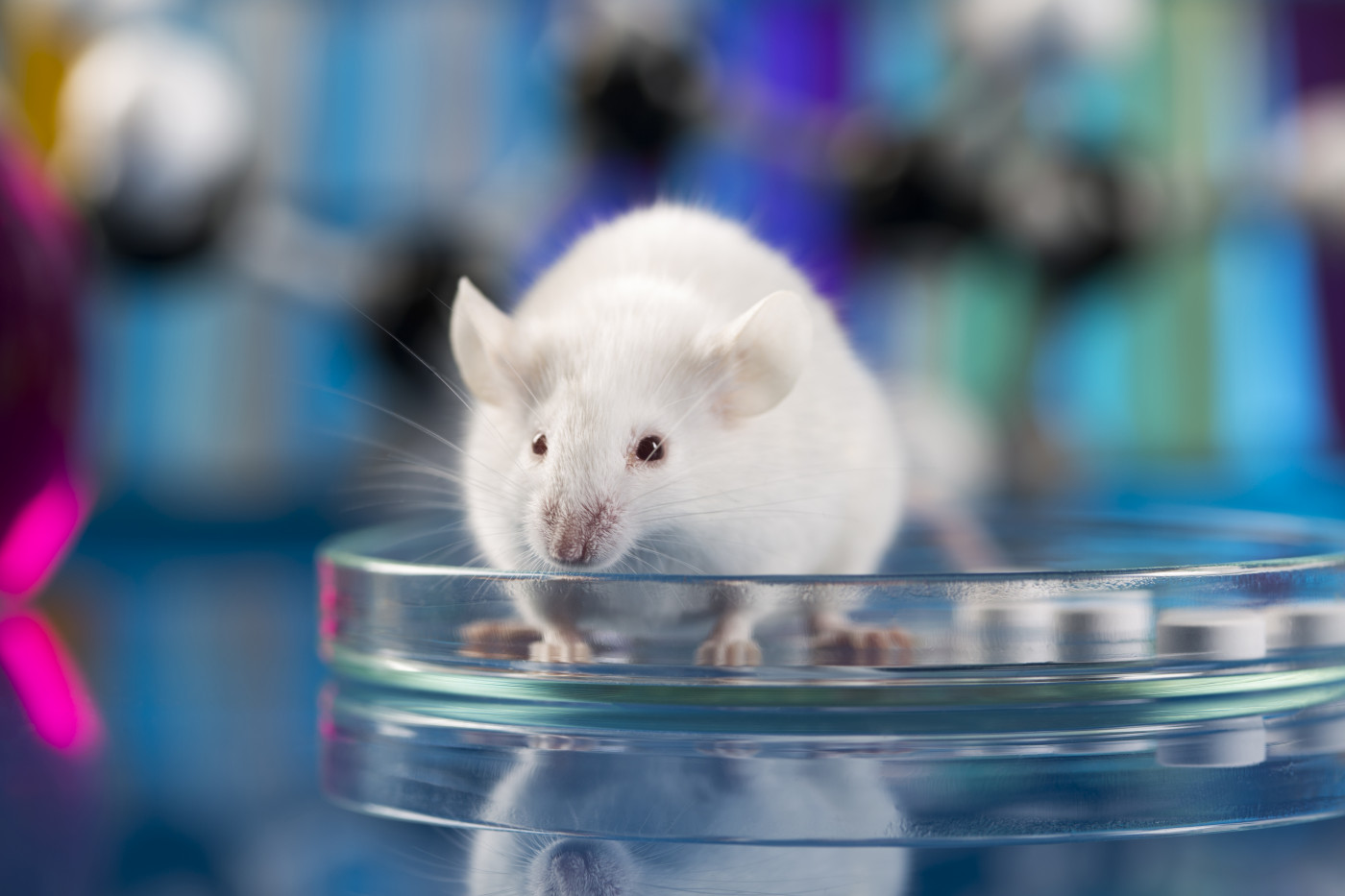

The researchers will test this approach in a mouse model of CMT2E, created and characterized in Garcia’s lab, that recapitulates many of the clinical signs associated with CMT2E, including severe gaiting defects, muscle atrophy, reduced axon diameter, and decreased nerve conduction velocity.

While the researchers will use mice for the preliminary studies, the model carries a mutated form of the human NEFL gene (called E397K) and the genetic material used in the gene therapy also comes from humans. Researchers also will use an approved U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) delivery vehicle to transfer the human genetic material to the mice’s target cells, which is expected to accelerate development.

Importantly, Lorson has effectively used similar genetic approaches for therapeutic applications — previously contributing to the advancement of Spinraza (nusinersen), an FDA-approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy.

“Together, this team represents a unique blend of experience in fundamental biology and “bench-to-bedside” science,” said Keith Fargo, chief scientific officer, CMT Research Foundation.

If the approach proves successful, the concept – that is, silencing the mutated gene and replacing it with the normal version – could be applied to other types of CMT, “whether the mutation is currently known or has yet to be discovered,” Fargo said.